Why the budget is disgraceful

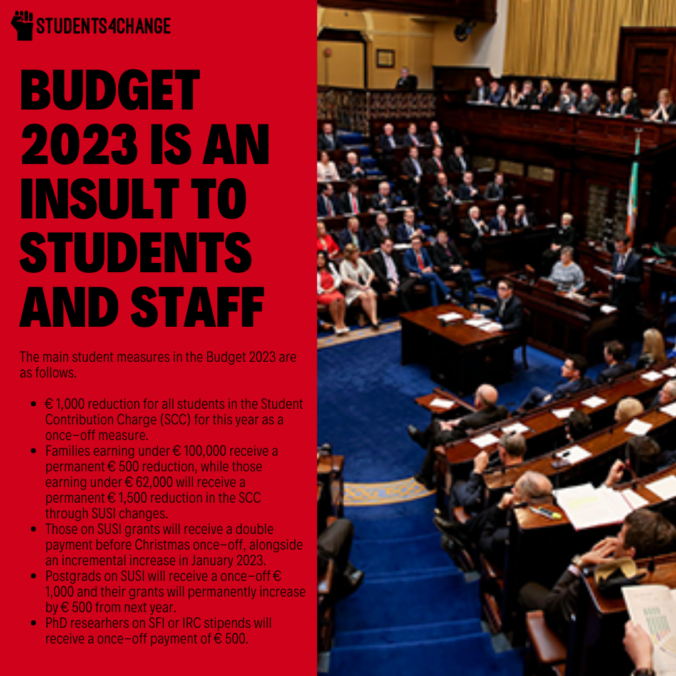

The main student measures in the Budget 2023 are as follows.

- € 1,000 reduction for all students in the Student Contribution Charge (SCC) for this year as a once-off measure.

- Families earning under € 100,000 receive a permanent € 500 reduction, while those earning under € 62,000 will receive a permanent € 1,500 reduction in the SCC through SUSI changes.

- Those on SUSI grants will receive a double payment before Christmas once-off, alongside an incremental increase in January 2023.

- Postgrads on SUSI will receive a once-off € 1,000 and their grants will permanently increase by € 500 from next year.

- PhD researhers on SFI or IRC stipends will receive a once-off payment of € 500.

We believe that this is an election budget, designed to garner appeal from young people and fool us into voting for the neoliberal coalition of Fine Gael, Fianna Fail and the Greens.

This is why most of the measures for students are once-off.

There is no real change in the budget and Simon Harris is breadcrumbing us once again.

We need holistic, permanent and structural policy change.

When it comes to the once-off reduction in the SCC, it is clear that the government are not committing to a publicly-funded third-level sector. If they did, they would have made the cut permanent. This once-off reduction will not alleviate the cost of education that is the highest across the EU, but the money quickly spent on rising cost of living and spiraling rents.

As the USI pointed out in their statement, the changes to SUSI grants will mean, in practice, that “the rate of SUSI will only go up by €8 a week for those on the non-adjacent rates”. For postgraduates, the relief provides pales in comparison to the cost of their degrees and the exploitation they endure. We need radical overhaul, not small tweaks.

Furthermore, the once-off payment of a meagre € 500 for PhD researchers is an insult. It is not enough. Researchers who contribute so much to academia continue to be underappreciated, undervalued and exploited.

Finally, there are no measures to tackle the student accommodation crisis. Students across Ireland are left paying sums of more than € 10,000. Out of 300 students that deferred at the University of Galway, 91 indicated it was due to the rental market. While permanent cuts to the charge for lower income brackets is welcome, without solving the housing issues they are simply not enough.

The Irish Universities Association (IUA) has pointed to the lack of core funding. The government itself identified a lack of € 307 million, but only provided € 40 million for the sector. The continued starvation of academia by the state will lead to intensified commercialization. At this rate, it will take 8 years for the third-level sector to receive the funding it needs.

Commercialization will mean higher rents, higher fees, more casualization, more cuts to vital services like counselling and no recognition of PhD researchers as workers and therefore no proper pay for them.

Historical Context

Third-level institutions acquire 50% of their funding from private sources, the highest in the European Union, due to a lack of public funding. Tuition fees for third-level were abolished in the mid-1990s, however, this has resulted in successive governments being tempted to slowly cut funding. While student numbers increased, so did taxpayer’s investments into academic institutions, but the overall money available per-student has been decreasing. For example, spending per student at third-level decreased from €10,806 in 2007 to €7,089 in 2016, a drop of 34.4%. This is despite the fact that between 2007 and 2016, public spending on education increased by 5.1% .

It is simply not enough, and this has resulted in the corporatization of institutions, where they have to make up for the loss of state funding by operating like for-profit businesses, cutting courses, downsizing services like welfare and putting up fees. Irish academia is at a breaking point.

Students and staff are struggling, while institutions are under immense pressure to perform with little to no funding. Despite the government’s commitment to plug the core funding gap, the € 307 million as announced in the latest plan Funding the Future falls half-short of what the 2016 Cassells Report identified as needed, and its implementation in Budget 2023 is even worse with only € 40 million given.

Furthermore, the plan stated that the Student Contribution Charge (SCC), in addition to non-EU and postgraduate fees, would continue to be a key part of funding. Despite promises, holistic change seems far away. Combined with the housing crisis and cost of living crisis, this risks the elitiziation of academia.

As the cost of education has increased, 11,189 students and their families have fallen in arrears during the Covid-19 pandemic across Ireland. The responses received to a series of FOI requests indicate a 67% increase in fee and university-owned rent arrears from 6,678 in 2018-2019 to 11,189 in 2020-2021. Reports are circulating that students are asking if they can pitch tents on campuses as a result of the accommodation crisis. It shows that students and their families are struggling across Ireland.

The student-staff ratio is 23:1 in Ireland and can be even worse depending on the higher-education institution, while the European average is 15:1. Students find themselves not receiving the proper one-to-one support that they need, and staff are stretched beyond their limits.

Institutions refuse to hire enough staff. Within the Irish third-level education sector, the average rate of casualization is 50%, with 80% of all researchers being on temporary contracts. They can be paid less than €10,000 a year. The average length of time spent in academic precarity in Ireland is 7.1 years for women and 5.7 years for men . The recent increase in college places has put further pressure on institutions, creating a situation where senior management accepts to take places for extra funding but there is no funding for the structures that would be required to deal with the influx, such as accommodation, welfare and sustainable cost of education.

Leave a Reply